Mainstage Chamber Concert • Thursday, July 20, 2023 • 7:30pm • Arkell Pavilion, SVAC

Sonata for Viola and Piano

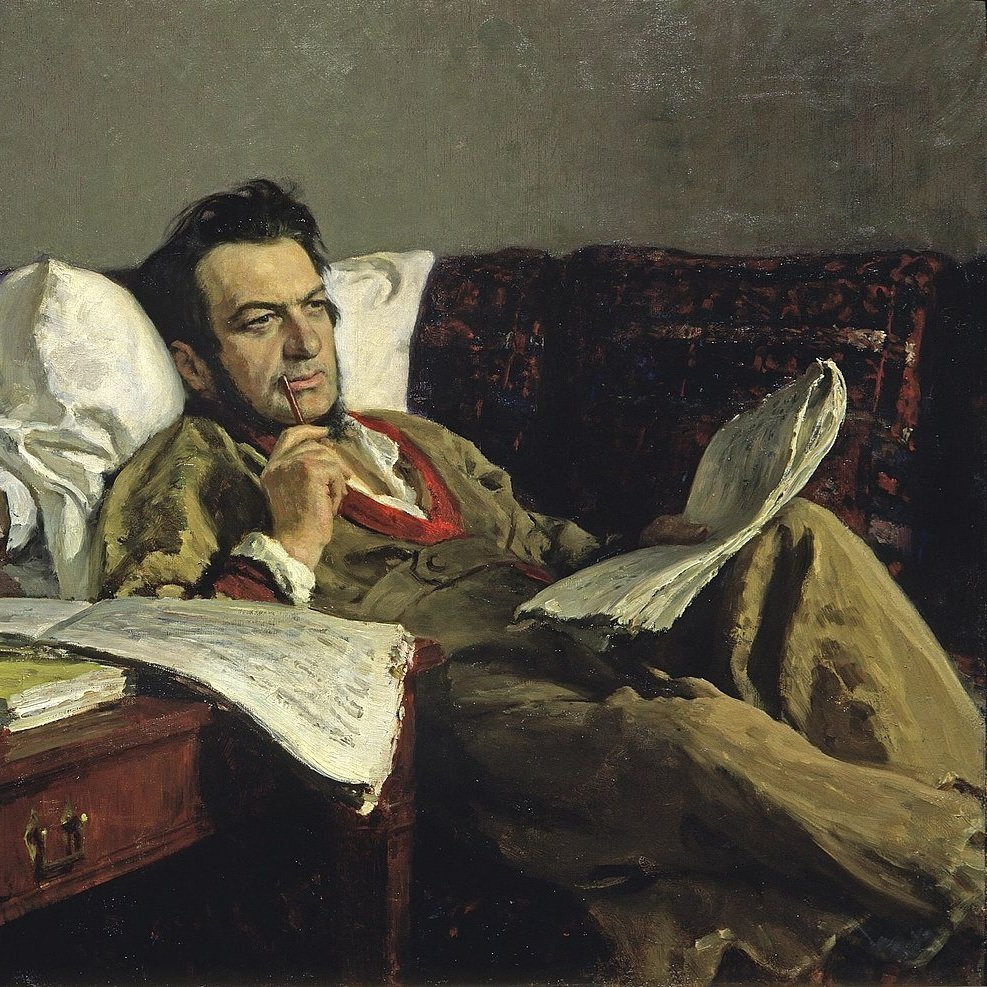

Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857)

Mikhail Glinka was the founder of Russian national music. Until his appearance, Russian musical life, especially opera, was dominated by such Italian composers as Domenico Cimarosa and Giovanni Paisiello, who had spent part of their careers in St. Petersburg. German musicians ruled the orchestras. The rich indigenous folk music culture was totally ignored.

Glinka, a product of the great wave of nationalism that swept Europe in the nineteenth century, changed the musical landscape with his first opera, A Life for the Tsar, the first opera on a Russian subject and the first to incorporate Russian folk idioms. Glinka followed up his first great success with Ruslan and Ludmilla, another opera on a Russian theme.

In spite of Glinka’s new take on opera, Russia still looked to Western Europe as its principal source of culture in all aspects of the arts. In 1830 Glinka embarked on the first of his many trips to the West where he sopped up influences that determined much of his subsequent musical output. A trip to Spain and France in 1844-47 included a study of Spanish folk music and a meeting with Hector Berlioz, produced such popular works as Jota aragonesa and Souvenir d’une nuit d’été à Madrid.

Unfortunately, Glinka’s productive life was short and his output meager, but his influence on the following generations of Russian composers was immense. He was the first Russian composer to be familiar and personally acquainted with the major musical figures in Western Europe, and was able to combine what he learned from the West with his roots in Russian folk music. His fantasy for orchestra Kamarinskaya, composed in 1848, served as model for Tchaikovsky who, 40 years later, noted in his diary that “All of the Russian symphonic school is contained in Kamarinskaya, just as the whole oak tree is in the acorn.”

The Viola Sonata, composed in 1825-28, consists of two movements only, an allegro and a larghetto. In a letter, Glinka said he planned to write a third movement, based on a Russian folksong, but the movement was never penned except for some preliminary sketches. The music is highly Romantic, clearly influenced by the German sound that dominated Russian instrumental music at the time. Glinka's "Russian" sound had yet to come.

Piano Quartet in B-flat major, Op. 41

Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921)

Composer, organist and pianist Camille Saint-Saëns was a man of wide culture, well versed in literature, the arts and scientific developments. He was phenomenally precocious and gifted in everything he undertook. As a child prodigy he wrote his first piano compositions at age three and at age ten made his formal debut at the Salle Pleyel in Paris, playing Mozart and Beethoven piano concertos. In his youth he was considered an innovator, but by the time he reached maturity he had become a conservative pillar of the establishment, trying to maintain the classical musical tradition in France and expressing open disdain for the new trends in music, including the “malaise” of Wagnerism. His visceral dislike of Debussy made endless headlines in the tabloid press. As a performer – he premiered his five piano concertos – his technique was elegant, effortless and graceful. But neither his compositions nor his pianism were ever a pinnacle of passion or emotion. Berlioz noted that Saint-Saëns “...knows everything but lacks inexperience.”

Saint-Saëns was a consummate craftsman and a compulsive worker. “I produce music the way an apple tree produces apples,” he commented. He was a proponent of “art for art's sake” and his views on expression and passion in art conflicted with the prevailing Romantic ideas. He wrote in his memoirs: “Music is something besides a source of sensuous pleasure and keen emotion, and this resource, precious as it is, is only a chance corner in the wide realm of musical art. He who does not get absolute pleasure from a simple series of well-constructed chords, beautiful only in their arrangement, is not really fond of music.” And also: “Beware of all exaggeration.”

Outmoded as he was perceived in his maturity, he was the first composer to write an original film score in 1908 for L’assassinat du duc de Guise (The Assassination of the Duke of Guise).

Composed in 1875, The Quartet contrasts a gentle and tranquil first movement with three fiery and rhythmic following movements. The two themes of the opening are similar in nature, rather than contrasting, and the whole movement has a laid-back atmosphere.

The slow second movement starts with loud staccato chords on the piano, countered by the strings in a somber chorale. The whole movement sounds angry, ending with three explosive fortissimo chords on all instruments. The scherzo has repeated episodes of Mendelssohn-like lightness, and the finale maintains the assertive mood, bringing back themes from the earlier movements towards the end.

The Quintet is actually Saint-Saëns' second. He composed one twenty years earlier, but it was not published until 1992.

Selections from Duos for Two Violins

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

Like his close friend, the composer Zoltán Kodály, Béla Bartók was concerned with the musical education of children. He composed many piano pieces for children, mostly based on his extensive collection of folk music from Southeast Europe and the Middle East, culminating in the monumental Mikrokosmos. Composed between 1926 and 1939 for his son Peter and comprising 153 pieces in six volumes, Mikrokosmos is a graded compendium with etudes for beginning to intermediate piano student.

Béla Bartók Jr., the composer’s son, wrote that “Although taking their ages into account, [Bartók] looked on children as full human beings. He sought to give them every possible help in improving their level of education. As far as music went, he tried to establish a basic musicianship in the malleable core of a child's character, which would enable the child to develop into a more worthwhile member of the human race.”

In 1930, musicologist and music teacher Erich Doflein (1900-1977) approached Bartók, requested permission to set various of the composer’s piano pieces for two violins, as part of a series of graded study pieces for young violinists. Under the name of music-educational theory, Doflein and his wife developed a system of progressive musical education that combined contemporary music and older music suited for teaching purposes. But Bartók preferred to write new duos, creating 44 works advancing in difficulty that he published in four volumes in 1933. All but two are based on authentic folk themes, including Hungarian, Slovak, Romanian, Serbian, Ukrainian and Arabic melodies. His goal was to present to young players the beautiful simplicity of folk music. While written with pedagogical intent, the pieces transcend their teaching aims to stand by themselves as perfectly poised works, with a wide variety of tempi and moods. Various groupings – some suggested by the composer – are frequently performed in concert.

Piano Quartet in A minor, Op. 1

Josef Suk (1874-1935)

As with many musicians who came from the provinces in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Czech composer and violinist Josef Suk’s first music teacher was his father, a local teacher and choirmaster. Josef entered the Prague conservatory at age eleven to study violin and composition, graduating in 1891 but staying a year longer to study with Antonín Dvořák. He was Dvořák’s favorite pupil and in 1898 married his teacher’s daughter Otilie. In 1892 Suk joined the Bohemian (later Czech) Quartet as second violinist in a career that ended about 4,000 concerts later with his retirement in 1933.

In January 1891, Suk became a student in Dvořák’s first composition class at the Prague Conservatory. Dvořák quickly recognized his talents, and when the students went on Easter break, he assigned him to write something for piano quartet. Suk completed the first movement of the Quartet, but only finished the first two sections of the Adagio before heading back to school. Dvořák admired the results, and Suk finished the work quickly and premiered it at the conservatory as his graduation thesis. Suk dedicated it to his teacher and it won a publication award from the Czech Academy the following year.

In spite of being only 17, Suk showed himself in the Quartet to have his own voice. His harmonic language was more progressive than his mentor's. The two themes of the first movement introduce a strong contrast. The first, by all four instruments, is vigorous and propulsive, the second, by the cello, is a gentle melody.

The second movement, opening with a gentle cello melody echoed by the violin, pleased Dvořák in particular. In the livelier, more passionate middle section of the movement, the piano takes a more prominent role, after which the gentle melody returns.

The piano dominates the opening of the finale, and it rules throughout most of the movement. Again, the harmonic language is more daring than Dvořák's.

Program notes by:

Joseph & Elizabeth Kahn

Wordpros@mindspring.com

www.wordprosmusic.com